Research and Treatment

The key to fighting AIDS is stopping the rapid replication of the HIV virus within a patient's T-cells, allowing an infected host to maintain a functioning immune system. A combination of three very powerful drugs, taken exactly as prescribed every day, effectively stops HIV from infecting new cells. While this isn't a cure, it means HIV-positive individuals can live a long and healthy life as long as they adhere to the treatment regimen. It's important to note that strict adherence is vital; missing even a handful of doses can allow HIV to begin replicating.

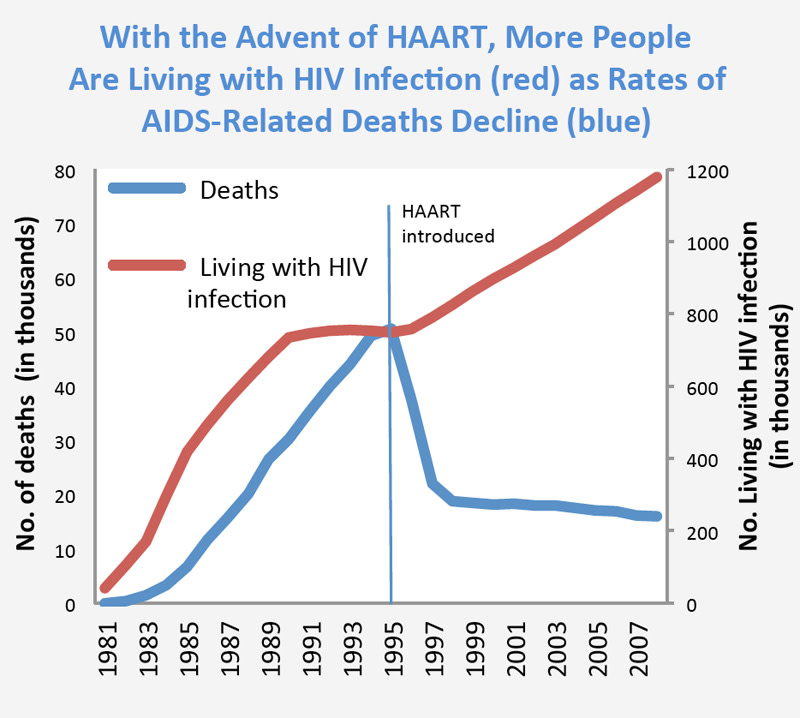

Image via the National Institute on Drug Abuse. While the number of HIV infections continues to climb, the development of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has significantly reduced the rate of AIDS-related deaths in the United States.

The first generation of AIDS drugs had some severe side effects; in fact, so much so that some patients were reluctant to start treatment. Today, side effects are significantly more tolerable and last only a few weeks in most cases. Typical short-term side effects include diarrhea, nausea and headache. Over the long term, some patients experience increases in blood sugar or changes in kidney function or bone density.

For anyone undergoing HIV treatment today, it is crucial to take the medications exactly as instructed, down to the hour of the day and to continue monitored checkups. Regular measurement of the viral load in the bloodstream can assure medical staff that the HIV virus has not begun to replicate into AIDS — the collection of potentially fatal illnesses and cancers that cannot be fought by an HIV patient's compromised immune system.

Inching Towards a Cure

The ever-elusive cure for AIDS may be within reach. Of course, as with any scientific research there are steps forwards and backwards in this quest. For instance, the global health community celebrated in 2009, when an HIV patient named Timothy Brown was reportedly cured of HIV after receiving a bone marrow transplant from a donor whose cells possessed a mutation for HIV resistance.

The success of this triumph has since been challenged by tests that find HIV has returned to Brown's cells. To compound disappointment, two doctors in Boston used the bone marrow transplant method to cure two AIDS patients, but the results were also temporary. HIV returned in the newly transplanted cells of both patients.

More recently, a baby who contracted HIV from her mother in utero was treated with antiretrovirals for most of her first year of life. Her parents discontinued her treatment and to date she is still healthy. Likewise, another HIV-positive newborn in Mississippi was treated at birth and remains disease-free, though scientists are unclear on exactly why. While the jury is still out on bone marrow transplants, treatment within hours of birth and other methods, the idea of a cure seems more realistic than ever.

In perhaps the most exciting announcement yet in the fight against AIDS, UNAIDS claims that by 2015 scientists will reach a crucial tipping point. Current estimates point to the number of HIV-positive patients in treatment exceeding the number of new infections. Throughout its history, the number of new infections has always far outstripped the number of patients in treatment. In light of this new data from UNAIDS, it looks like scientists may finally take the lead in the battle against the global AIDS epidemic.